I became enamored with Texas native Roughleaf Dogwood, Cornus drummondii, during the time I managed the Green Garden at Austin’s Zilker Botanical Gardens. I knew about “Texas” dogwood, an understory small tree or shrub which blooms in spring and produces white fall fruits, but I had never planted one of my own. Nor did I originally pay attention to the stunning specimen situated in the woodlands plants section of the Green Garden, set back from the formal pathway. I recall the golden leaves which brightened the dogwoods’ limbs, and then the ground below it, during the December after I was hired. But it was in spring that the puffs of creamy dogwood flowers really caught my attention. Snowy floret clusters gracefully adorned the slender limbs of the Zilker dogwood, the little tree set off from a well-worn path to another Zilker garden, nonetheless demanding attention from passersby.

I was smitten.

I mulled purchasing my own little dogwood, but a gardening friend (thanks Deb!) gifted to me a seedling C drummondii from her Westlake garden. I planted my baby dogwood in the center-back section of my back perennial garden. Eager for it to grow up, I waited. And waited. Truthfully, it didn’t do much in the growth department until I removed a tired, old Tacoma stans ‘Esperanza’ that had been, for many years, the main actor in that garden and whose size hampered the growth of the dogwood. Once Tacoma was gone from the garden, the Roughleaf Dogwood grew apace and came into its own.

I eventually added a second dogwood, purchased from a local nursery, and placed it at the back of the pond.

Since then, I’ve practiced botanical pay-it-forward by digging up and gifting my own dogwood starts to other eager dogwood lovers, plus I’ve planted one more in a different part of the back garden.

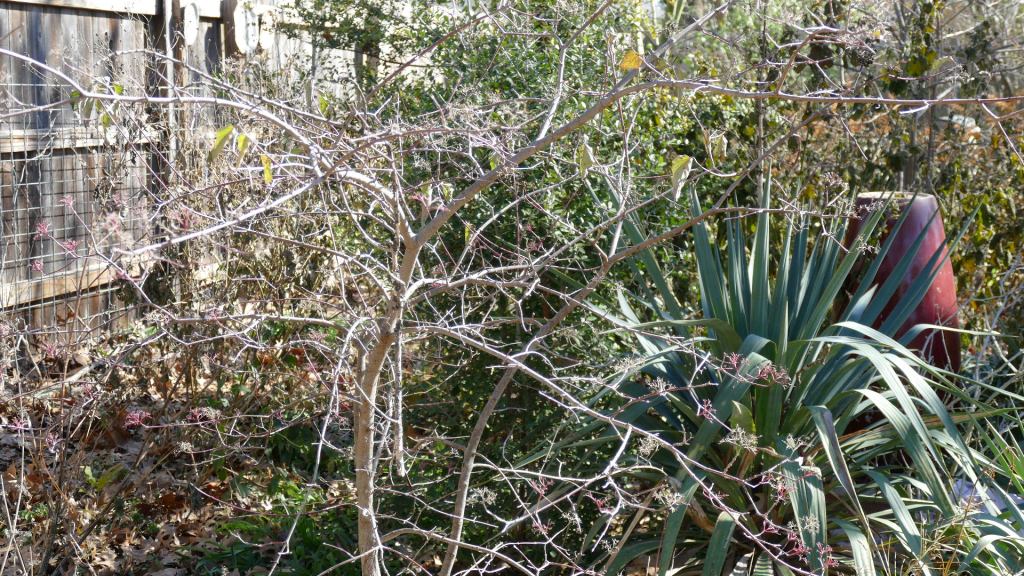

Roughleaf Dogwood is deciduous, which means leaves drop after the first freezes of the winter season. Multi-limbed with slim, spidery appendages, the tree can be prune for shape according to human preferences.

As I’m an admirer of nature’s evolutionary practices, I don’t typically prune much on my dogwoods, unless an extremity is nudging up against another plant in a way I find bothersome. Years ago, I’d read that dogwoods had a tendency to colonize out in a garden situation. In its first decade (under the shadow of the T. stans) that was never a problem. But as my first dogwood has matured, there are root-bound outreaches of new trunks.

Some of these I’ve dug up and either gifted or composted, but the ones near the original trunk I’ve let remain. Any that pop up further away from the mother plant I prune back to the soil once or twice each year; newbie trunks are easily spotted in winter. I could dig them out, but they’re a bit too deep-rooted for my back to handle, so it’s a snip-to-the-top-soil for these potentially pesky wannabee trees. If you have a larger space, let them go to grow, bloom, set fruit and be dogwoods. According to the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, various songbirds nest in dogwood thickets, so that’s a great reason for allowing thickets to develop–if you have the space. But for those in more restrictive urban plots, some management of dogwood enthusiasm is a must.

In early spring, usually March, the first, verdant leaves appear: tiny, bright green and delicate. Often, the branchlets that held last season’s flowers and fruits are still attached to the awakening tree.

The spring green leaves make a statement about the longer and warmer days settling in.

Flower clusters follow, though they take time to develop to the point of offering open blooms for feeding wildlife and admiration by humans.

The flowers are constantly visited by a wide variety of pollinators.

I see a multitude of flies and native bees on my flowers. Honeybees and skippers are also frequent sippers of the nectar provided. Sometimes, butterflies rest on the foliage.

The bloom season lasts into May for my two plants.

Hot summer months see the dogwoods as lush and green, water-wise, and a good place for birds to rest.

By late August/early September, luscious, creamy fruits are available for both resident and migratory birds.

I’ve mostly witnessed Blue Jays and Northern Mockingbirds at the berries, but they’re sneaky about nibbling while successfully hiding behind branches and clusters of leaves.

Usually by late fall, no fruits are left on either of my dogwoods; this is when foliage color show commences. Shorter days and a couple of light freezes trigger dogwood foliage color changes, and is always reliably lovely. Typically, the early foliage color are yellows and pastels.

In time and with ongoing cold temperatures, deep burgundy covers many leaves, the dramatic colors remaining until leaf drop.

January and February bring bare dogwoods.

Bare limbs allow for easier bird watching.

Roughleaf Dogwood is native not only in Texas, but throughout a wide swath of the United States and also in Ontario, Canada. I’ve never experienced any disease or insect issues with either of my trees and drainage hasn’t been an issue. Roughleaf Dogwood is a tough plant which remains lush and green throughout our hot, long summers. It is not deer resistant.

If you have the room in your garden, plant this lovely small tree or shrub. Roughleaf Dogwood is an ideal urban native plant. It’s easy to grow, provides for wildlife and is an attractive plant.

In Spring:

Summer:

Autumn:

Winter: