June 16-22, 2025 is Pollinator Week, celebrating the importance and beauty of pollinators. Pollinators share outdoor space with humans (and other critters!), but are in decline due to a variety of factors, including habitat loss, use of chemicals, and climate change.

But in your own space of a home garden, in nearby public park or school garden, even a small to medium sized pollinator garden attracts multitudes of pollinator participants and adds a bit more beauty and life to the world.

It’s easy to attract pollinators–just plant things they like to pollinate! Native plants are always best because they usually require less water and effort, and native plants are appropriate in their range. Also, native plants are beautiful.

Hardy, non-natives are also on many pollinators’ yummy lists, so roses, daylilies, irises and other similar plants are often good choices for a garden.

In most areas of North America, pollinators are active throughout the growing seasons, including winter in some places. Here in Central Texas, I’ve found that pollinators increase in number and variety as spring segues to summer, then morphs into autumn.

Autumn bloomers are important sources of nectar and pollen before winter sets in. Late summer/autumn blooming perennial shrub, Frostweed, Verbesina virginica, worked by a honeybee, whose corbiculae (pollen pantaloons!) are filled with pollen goodness.

Pollinators and pollinator plants come in all shapes, sizes and varieties. Trees produce flowers for pollinators when they bloom, no matter the season.

Shrubs, perennials, annuals, and ground covers are also in the pollination business.

Most folks recognize that bees (both honey and native), butterflies and moths are common pollinators. But flies, ants, beetles and true bugs are vital pollinator sources and should be welcomed in any garden space.

To have grown-up pollinators visit your garden, specifically with butterflies and moths, first there must be babies. To feed those young’ns, host plants are required and should be part of any pollinator ecosystem. Yes, foliage will be munched, but it’s a rare event that host plants are eaten to their end by the insects that the host plant nurtures.

Many herbs and common garden plants are host plants for pollinator insects. This is why it’s a BIG no-no to use pesticides: if you spray for caterpillars, or other “bugs” eating the foliage, it’s likely that you’re killing future pollinators. Remember and repeat: most insects are benign, many are beneficial. So skip the stinky aisle in the big box store and avoid pesticides in the garden.

Check out https://www.butterfliesandmoths.org for information on the kinds of host plants specific to butterfly/moth species. It’s a great go-to site for all things butterfly and moth.

There are honeybees,

…and there are thousands of native bee species.

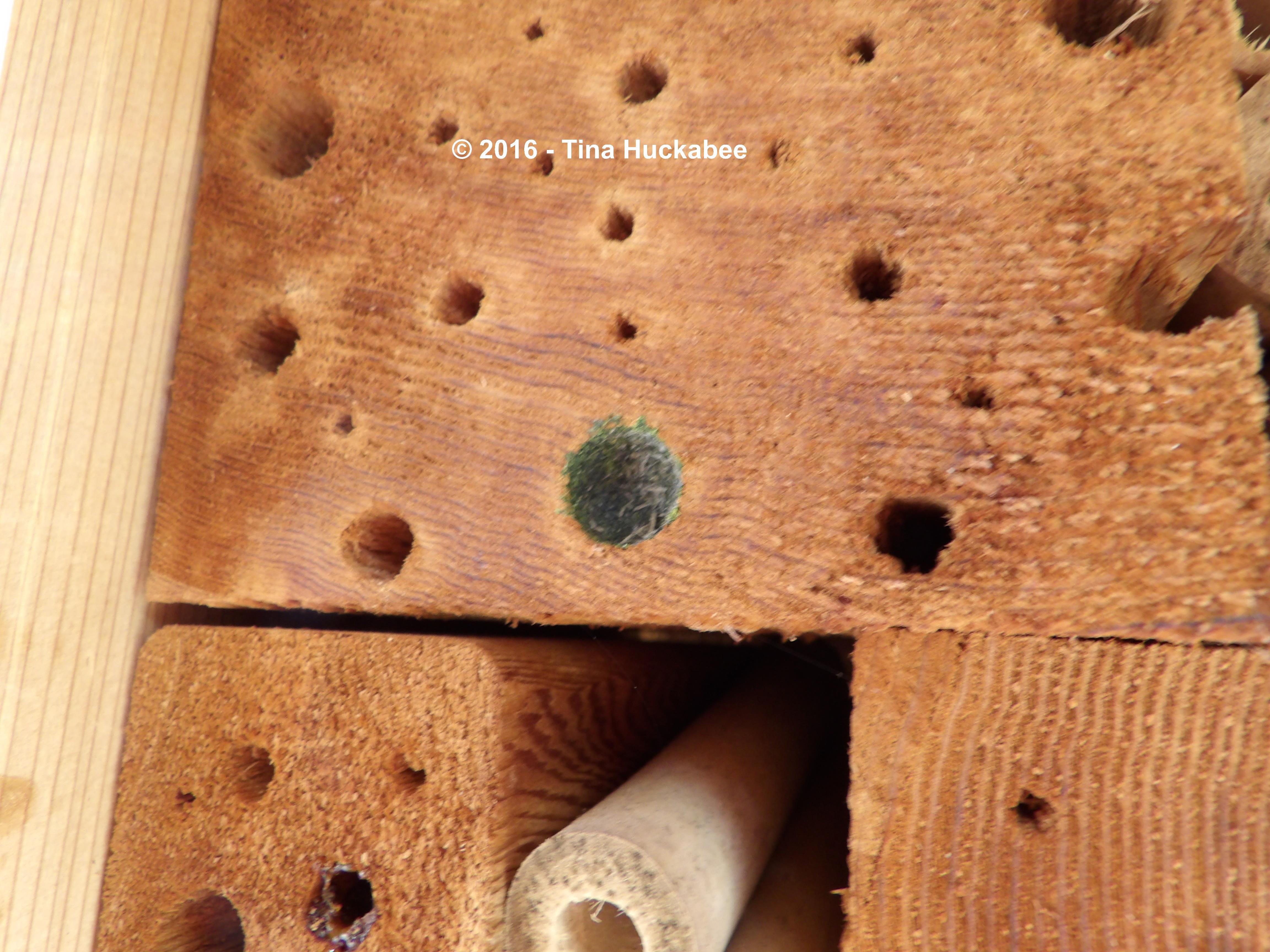

Native bees are generally solitary and nest only for their offspring, unlike honeybees who nest in large collectives. Native bees nest in the ground, in wood, and older stems of plants. You can help natives find spots for reproduction by leaving some wood in your garden, by allowing some soil to remain bare, free of plants, mulch, and ground-cover, and also by delaying winter pruning until just before spring growth. You might also want to build bee “houses” or “hotels” which will provide space for many bees to nest.

In short, most garden plants that flower will attract insects, the good kind, and especially pollinators. There are a few tricks to a successful pollinator garden project, but creating a garden is a learning experience and a creative endeavor. Check out your local plants, see what you like and what would work in your space. There’s a great deal of accessible plant, insect, and design information to help you on the way. To create a pollinator garden, research and learn, then unleash your imagination and artistic self and be prepared to perspire. Then have some gardening fun and help heal the world in your own back yard!

If you plant them, they will come!