Winter placed its chilly hands on the garden these last two days, including gifting a thin layer of ice in the backyard birdbaths this morning. But the weather pattern is in flux with each passing day as the march toward winter’s end and spring’s beginning commences here in Central Texas. Later this week, the forecast is for high 70s, possibly warmer. Even without that warm smooch, the plants in my garden are raring to go and ramping up for the 2024 growing season.

On a cloudy day last week, I noticed (as yet uneaten) fruit on the Possumhaw Holly, Ilex decidua, keeping company with emerging new foliage. I like this great example of seasonal transition period. Blue Jays, Northern Mockingbirds, and Grey Squirrels are feasting on the fruit, but I’m waiting for a flock of Cedar Waxwings to swoop in and render the fruit a sweet memory.

Four-nerve Daisy, Tetraneuris scaposa, never stops blooming, though some of mine were freezer-burned in January during a very cold week. Now? The sunny yellow blooms are spring-bright and open for pollinator business.

This small (maybe?) native Halictidae bee found a sweet spot for nectar sipping and pollen gathering one afternoon. I didn’t disturb its hunt for the sweet stuff as I puttered in the garden.

Four-nerve Daisies are barely damaged by most freezes, but in the above photo, on the right side, you can see a bloom stalk that would have flowered in late January, except for that one deep-frozen week. The other bloom stalks emerged post-hard freeze.

On another day, another, different native Halictidae bee, busily works a daisy bloom.

Some of the earliest blooms in my garden (and occasionally some of the latest) are Spiderworts; a handful have emerged from green foliage to grace the garden and feed hungry pollinators. A favorite early flower for many types of bees, from mid-March until mid-May, my garden will be awash in an array of purple-to-pink blooms.

Those plants whose blooms appear later in spring and summer are flushing out with verdant foliage, like this rosette of Blue Curls (also called Caterpillars), Phacelia congesta.

A couple of young Blue Curls accompany a robust rosette of American Basket-flower, Centaurea americana. Both promise plenty of flowering and pollinator action later this year. The rich green foliage is a welcome change from winter’s muted tones.

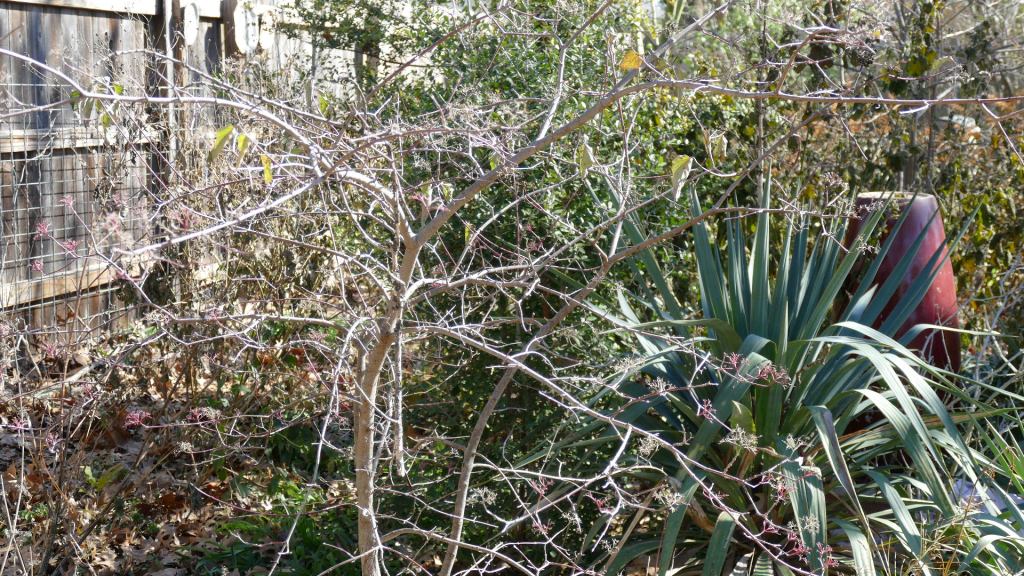

This potted American Century Plant, Agave americana, enjoys some foliage friends in the form of one European Poppy (right), a Blue Curl (left), and a front-n-center Carolina geranium, Geranium carolinianum.

I grow five Desert Globemallow shrubs, Sphaeralcea ambigua. This gorgeous plant is a cool season bloomer here in Central Texas and requires full, blasting sun and decent drainage. Ruffly, sage-green leaves pairs beautifully with Dreamsicle orange blooms.

This globemallow withstands hard freezes, but if the temperature falls in the the teens–or lower–damage will occur. My shrubs experienced some freeze damage in January’s freeze, but all are producing blooms on the healthy stems–much to a variety of bees’ delight.

Honeybees are out and about, collecting for the the hive!

I fed the honeys during that cold week, but there’s been enough flowering (I think…) during most of this winter, plus both hives had honey stores. Our first hive check is on the to-do list for this next week to assess how the ladies are and how much honey, if any, remains from last season.

I’ve been engaged with winter pruning of the garden, but I’m nearly done. I let leaves remain on the ground, further protecting and nourishing life, and eventually decaying for future growing seasons.

The garden has awakened, its inhabitants ready to live and reproduce. Plants and critters are in sync with their companion life-cycles.

It begins, anew.