In early June, at the first hive check of the month (we check our hives every 2-2.5 weeks from late February through October), we realized that there was no activity around our hive, Woody. No bees were flying in, no bees were flying out. The hives sit at the back of the garden and I don’t garden-putter much in that area, so day-to-day, I don’t pay close attention to the honeybee goings-on.

When we opened up the hive, it was empty of life. The comb was beautiful and intact and the bees had eaten all the honey in the the 30 frames, there wasn’t a drop left! Woody’s bees had absconded, meaning that the hive performed a total swarm: the queen and all the workers left, permanently, and for unknown reasons. Honeybees will abandon their hive if the resources are scare (not in this case), or if there is prolonged, rainy weather (didn’t happen), or for other, only-for-honeybees-to-understand, reasons. Bingo! We believe the hive absconded just a few days before the planned the hive check and during the previous hive check, Woody was a healthy, active hive.

The one issue that could have have caused Woody to search for and move to different real estate is that the stronger hive, Bo-Peep, might have been robbing Woody of its honey, and perhaps Woody’s ladies had enough of that nonsense. Realistically? We’ll never know why the bees left. Absconding happens, not often, but it’s a natural process, akin to honeybee swarming, though with different causes and goals. Woody’s absconding is our first experience with this particular honeybee happening.

We dismantled the hive, laid the parts–boxes and frames–in the garden, preparing to freeze the frames to kill any wax moths or other invasive insects and their eggs. We’ll wash the hive boxes with a bleach/water mixture to kill eggs snuggled in cracks and crevices.

I should add that we don’t think the bees absconded because of wax moth eggs or larvae that were in the hive. Every hive in Texas has wax moth eggs and at least, early stage larvae. Wax moth larvae are truly nasty critters, but a healthy hive will keep the hive free of an infestation. Bees are tidy gals! Weak hives are vulnerable, and empty wax frames just sitting around are an invitation for moths to lay eggs so that the gross caterpillars eat their way through the wax.

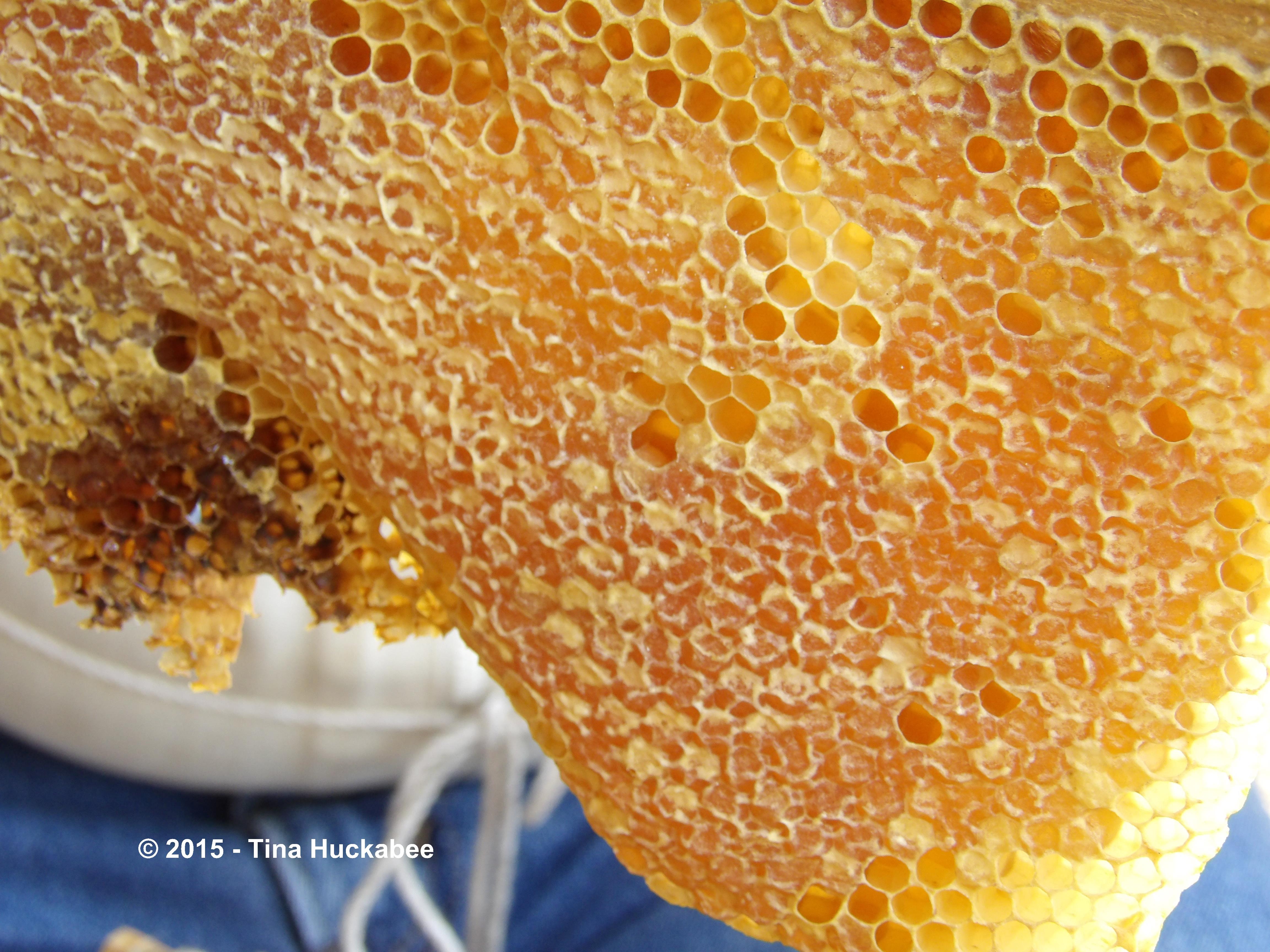

Even in the few days that the bees weren’t in the hive, wax moth larvae had hatched and commenced with their wax destruction. The larvae eat the wax, leaving frass and webbing as they move through the comb. A serious infestation will destroy a hive in a matter of days. We lost a hive to wax moth several years ago and it was horrific. It was one of the foulest, most disgusting clean-up chores I’ve ever been forced to engage in.

If you look carefully at the comb cells, you can see some of the small, newly hatched larvae.

The larvae grow to about 1 inch long and are quite plump before they’re ready to pupate and morph to their adult selves. Freezing the frames for 3 days is the best insurance for killing any eggs or larvae. Each time we take honey frames for extraction, we pop the frames into our freezer for the allotted 3 days; afterwards, we store the frames in plastic bins. We extract as soon as we have time (it’s a process), because no matter how tight the lids are, if we don’t extract within a month or so, wax moth larvae somehow appear, even when we’ve taken correct precautions.

Bo-Peep is now our only hive.

Bo is a prolific honey producer. This season, we’ve already extracted over 6 gallons of honey from her and we have 5 more frames ready to process. I’m hoping that at the next hive check, we won’t need to take honey to free up space in the hive, but we’re going to make sure we have a few frames ready for replacement–just in case! We want to leave plenty of honey for winter, but also to allow for space in the frames so that these busy bees will continue to do what they do–pollinate, slurp nectar, and make honey–in the cooler season ahead. Bees are honey hoarders and they force us to be honey hoarders!

They just can’t help themselves…