It’s the first Wednesday of the month and time to celebrate those wild things who live in, visit, and NEED your garden! Welcome to Wildlife Wednesday for February. I’m still enjoying my backyard birds for Cornell Lab, but didn’t want to bore with the usual suspects from last month, though I have witnessed a Sharp-shinned Hawk, Accipiter striatus, visit a couple of times, no doubt looking for a tasty bird meal. I was too excited to grab the camera, so there are no pics of that gorgeous raptor staring hungrily at the White-winged Doves.

Because it’s deep, dark winter,

…or not, I thought I’d share a project that Bee Daddy and I undertook this past year. It’s not related to our honeybees this time ’round, but to our beautiful native bee residents. I’ve long left well-aged wood in my gardens so that bees can make a home for their offspring. It’s easy to do: leave wood out in the garden for bees to find.

They drill into the wood,

…to lay their eggs and then tuck those eggs in with pollen, soil, and such, and voilà,

…more native bees are made.

I do so love my honeybees. But the fact is that honeys are lazy pollinators and if you want bees with pollinating pow-wow, you need to attract whatever bees are native to your area of our little planet. Native bees are the best pollinators around. They pollinate food sources (one in three or four bites of food, depending upon your reading source) and approximately 90% of native plants are pollinated by native bees.

Native bees are vital for the health of the world.

According to the US Geological Survey, there are roughly 20,000 native bee species in the world, about 4,000 of which live in the U.S. They do not suffer the many maladies of honeybees, but we know that they are declining. The decline comes primarily because of human encroachment on natural areas, the move away from using native plants in home and commercial landscapes, and pesticide use. Additionally, native bees nest in wood and in open ground–all places and things that most folks rush to scrap in their home gardens. The sterile, pristine landscape paradigm is not kind to wildlife–of any sort–but it’s especially unkind to native bees. Wild bees need wild space. There’s not much we can do about urbanization, but gardeners can easily make our home landscapes amenable and attractive for these incredibly valuable and fascinating insects.

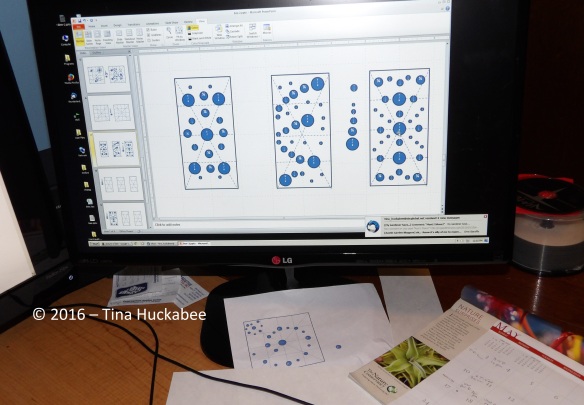

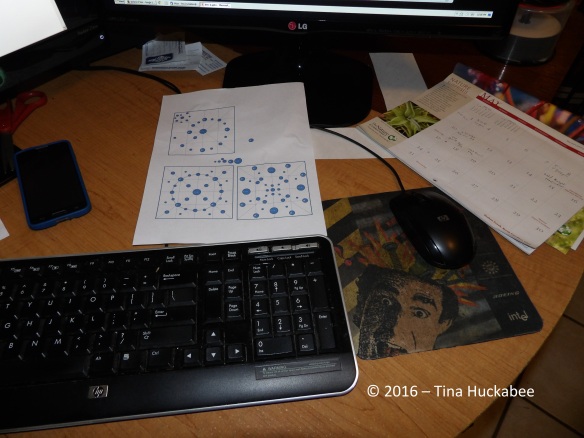

Last spring, Bee Daddy and I designed templates for wood cuts of varying circles sizes and patterns on the computer,

…that we (okay, Bee Daddy, not I) then drilled into cut, untreated wood.

The wood doesn’t need to be expensive (Bee Daddy used inexpensive fence pickets and 2×4 boards), but it shouldn’t be treated with any chemicals. Remember, we’re trying to make nice homes for bees, not homes laden with icky, insect unfriendly chemicals. You want to drill a variety of circumference sizes as well as varying depths for the holes in order to attract different species of bees.

Additionally, we (okay, Bee Daddy, not I), cut various sizes of bamboo (harvested from a friend’s home who was glad to share) to insert between the holey wood.

Ta da!! A bee/insect hotel! Or townhouse! Or apartment! Or condominium! Or nesting box!

Whatever!!

What this bee house really does is create something cute for gardeners to look at and safe for bees to nest in and nurture their offspring. Native bees rest-n-nest in a variety of situations like the ground and natural cavities of wood or even rock. People-made insect hotels have become popular garden-art additions for those wild gardeners wanting to attract even wilder bees, as well as other important garden residents.

I stacked the two insect hotels for “my” native bees, one on top of the other, with both popped atop an unused and upturned terracotta pot. Many insect hotels are free-standing and some are made to hang on fences or posts.The insect hotels can be as elaborate or as simple as your time and interests allow for. My bee condo is situated in a shady spot and both stories have a little overhang so that the entrances to the holes are somewhat protected from weather conditions. The different sized holes assure that bees of all kinds can find refuge for their young. Additionally, lizards and other insects will probably use this as a shelter and also to hunt critters who happen by.

Such is nature.

Don’t have a handy honey-do, carpenter-happy Bee Daddy to do the drill-baby-drill part of this project? That’s perfectly okay. Aged firewood, or smaller, broken or trimmed tree limbs make great homes for native bees–and all you have to do is place these soon-to-be-bee homes in your garden and the bees will come.

Can you see this little gal, squirreled away in her hidey-hole?

Available wood makes life easier for bees like this female Horsefly-like Carpenter bee, Xylocopa tabaniformis. .

This mother-to-be drilled all afternoon one day last spring, only to abandon her nesting site. I hope she found softer wood here in which to lay her eggs.

On my back patio, there are holes in the limestone rock that were drilled for shelves that we removed some years ago. Instead of filling those holes with mortar, I’ve left them open and I’ve seen several species of bees use these holes as nurseries for their off-spring.

Nice! I’m looking forward to viewing whomever emerges from that hole and who will be a pollinating fool all spring, summer, and fall.

Along with setting out wood or building insect hotels, if there are fallen leaves from autumn, on the ground waiting for “someone” to pick them up–don’t! Or, at least, leave some leaves on the ground. Better yet, place that fallen foliage in your gardens. Many insects, including bees, take refuge in the cover that crinkly leaves and small tree limbs provide. Plus, the leaves don’t end up in the landfill and it’s less work for the gardener if the leaves aren’t bagged.

“Less work” for the gardener is always a good thing.

Lastly, don’t be shy about allowing some open dirt space in your habitat. There’s no garden rule that says every square inch of your property must be mulched, gardened, turfed, or hardscaped. About half of native bees are ground nesters and some of the most threatened native bees are those that need bare ground, either to over-winter in or to nest in. You’ll do everyone a favor if there’s a little naked dirt on your property, here and there.

As of now there are no residents in our native bee houses. Because life gets in the way, it took us a while to complete this project: we made the templates last May, but we (okay, Bee Daddy, not I) finished the frames, bamboo cuts, and holes in November. I imagine there will be some residents in place by late spring this year.

For more information about building your own native bee/insect house, check out this link from the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. There are many Internet sites with information about native bees and how to make insect hotels. If you have children, this is an especially fun project in which to include them and teach the importance of nurturing wildlife and providing habitat.

Don’t forget to plant gorgeous native plants for your bee buddies to nectar on.

Lovely non-native bloomers also fit the bill and provide for pollinators.

The world will be a better place for their survival because of your efforts.

Did wildlife visit your garden this past month? Please post for February Wildlife Wednesday–share the rare or mundane, funny or fascinating, beneficial or harmful critters you encounter. When you comment on my post, please remember to leave a link to your Wildlife Wednesday post so readers can enjoy a variety of garden wildlife observations.

Happy wildlife gardening!