As good beekeepers, we follow advice from those who know more than we do–which includes the vast majority of attendees at the monthly Austin Area Beekeepers Meetup. The advice this month was to open hives, check out the gals, see if they’re starving or if there’s honey left over after winter, and institute swarm management.

That term sounds like something you’d hear in a leadership management course. Ugh.

Swarm management. It’s basically crowd control. Perhaps more accurately, a kind of birth control. A honeybee hive is a superorganism. A superorganism is a collective of individual organisms which work together as a whole, where the individuals cannot survive without the collective. The way a hive procreates is to divide itself by swarming into a new hive. A new queen is anointed, she leaves the hive, taking workers, maybe as many as half the workers, with her to happily settle in a tree hole or ceramic pot, as happened in the garden of a friend of mine. Swarming is not something we want for our bees. At some point in the future, probably next spring, we plan to hive our bees into one or two Langstroth hives, eventually ditching our Warre hives. That’s not happening this year–we don’t have time to build new hives.

So as part of our swarm management responsibilities and because it’s simply time to see how the ladies are faring, we opened our hives to check for any leftover honey stores, to see if our queens are laying eggs with resulting larvae, and if there are any queen or drone cells developing.

On Valentine’s weekend Bee Daddy and I donned our bee suits,

…fired up the smoker,

…organized our honeybee paraphernalia and got to it.

As a refresher, our hives are Mufasa and Scar.

For those of you who are parents of a certain age, these names will be familiar–from the overplayed Lion King movie which was released in 1994 and by 1995 was on DVD (remember those?) and that a little tiny girl watched while Mommy held the new baby brother. At least, that’s how it was at our house.

The names were given (in the case of Scar) for obvious reasons–oops that table-saw blade pulled the wood right out of Bee Daddy’s hand, leaving a scar on the wood and a partially numb finger on the Bee Daddy.

Yes, there was lots of blood and a long afternoon visit to our local Emergency Room.

Mufasa is so named because that’s the obvious next choice.

This was the first full hive-check in quite a while as we haven’t opened the entirety of each hive since re-queening last July. This February examination was a complete physical, if you will. Mufasa was first on our list of hive appointments. We took off the top box and there was only empty comb.

I knew that already because I’d peeked in there occasionally on the warmer days of winter. Mufasa has always been our smaller, less hardy hive, so I wasn’t surprised or disappointed that the bees hadn’t mustered the numbers to honey-ize the top box. Off it went, stored for later use in the season. If all goes well–good flower production and pollen/nectar gathering in conjunction, we’ll pop it back on later in the season.

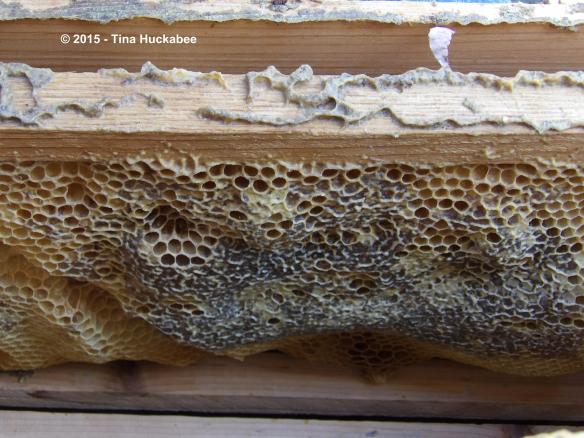

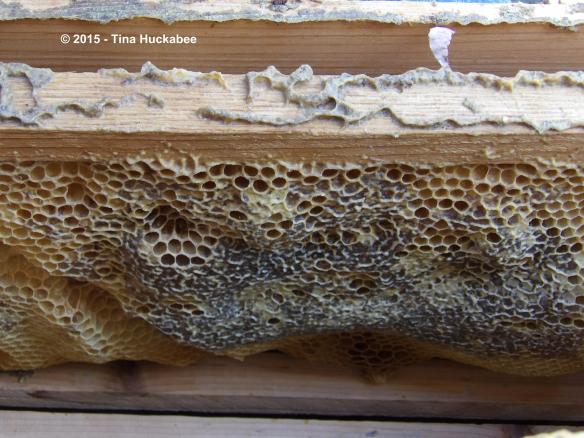

Then we checked the second, or middle box.

A side story: In September, as we checked our hives, a comb with full, capped honey broke, which I decided to leave in the box as is, knowing that it wouldn’t be easy to extract once the bees reconnected it to the box. You can read about the dropped-comb incident here. Now after winter, the time of reckoning is at hand–we must carefully cut each top bar with comb, to check honey stores and brood development. And that check includes the cross-comb developed from the dropped comb.

Oh, the stress of it all.

After slowly and carefully cutting away the comb from the sides and the bottom of the box (which directly attached to the bottom brood box), we were very happy with the results.

Mufasa’s second/middle box was moderately full of capped honeycomb, with some empty ready-to-be-filled comb.

We removed the cross-comb and cut the comb off a couple of the top-bars.

… and bagged some rich honeycomb for later honey extraction work in the kitchen.

We left some comb with honey and some empty comb so the bees have honey on cold rainy days and room for brood and more honey stores–whatever is their preference. Both of those goals are in keeping with swarm management–give ’em room to grow, so some of the more rebellious members of the hive don’t have an excuse to leave home.

Finally, we checked the bottom, or brood box and what good news for Mufasa and tangentially, for us!!

Whoop!! Queen Mufasa (the name suggests a little gender bending there–Mufasa was a dude lion, Queen Mufasa is a queen bee), is ramping up for spring, laying eggs and the larvae are growing and developing. You can clearly see that there are capped and uncapped larvae.

What a great queen she is and how ’bout those workers, eh?

The development of adult bees occurs in stages and is driven by pheromones according to what hives need: workers, drones, or queens. Capping instigates the final stage in development–what emerges two to three weeks after the egg is laid is an adult bee. All of these are workers (because of where they’re located and how they’re capped) and the hive will need workers once spring nectar flow begins–in about three weeks. The timing is perfect! We didn’t see any queen cells, which is a good sign. Queen cells develop on the sides or bottom of the comb and are larger and oblong–very different from what the photos here show. That no queen cells exist signifies that the bees are content with their queen–she’s healthy and laying eggs and everyone, it appears, is down with that.

We closed Mufasa,

…grinned, did a little dance and high-fived each other, then moved onto Scar’s examination.

It was, essentially, more of the same. Lots more. In Scar’s top box, all eight top bars were full of capped, glorious honey.

Heavy, heavy bars of honey.

We removed all eight, cut the comb, bagged it and stored the box for later use. The second box was similar, though some comb was empty. We left some full honeycomb, as we did with Mufasa. The brood box was also full of good news. Like Mufasa, Scar contained capped and uncapped brood, no queen cells, and stored honey.

I’d call the examination of both hives a good day at the office. Both Mufasa and Scar have a brood box and a secondary box for expansion. If the year goes well, the bees will produce enough brood, honey, and comb that we’ll add another box in late summer or early fall, just like we did last season. I don’t think that far ahead though–there are too many factors and variables in beekeeping. For the present, in late winter, the immediate future looks good for both hives. Fingers crossed that success continues into the new year and growing season.

Time to clean up and,

….what do I do with all that honeycomb????

Honeybees and all other pollinators need us and we need them–our survival depends on their survival. There are simple things that gardeners/homeowners can do to help declining pollinators, birds, and other wildlife:

Honeybees and all other pollinators need us and we need them–our survival depends on their survival. There are simple things that gardeners/homeowners can do to help declining pollinators, birds, and other wildlife: