I last posted about my honeybee hives in April, describing with awe the drama of a swarm out of, and then back in to, Buzz. That event morphed into several months of beekeepers’ head-scratching and eventual realization that something wonky happened in Buzz and that our remedies to fix the wonk proved futile. Rest assured that Scar, one of our original (Warre) hives, and Woody, our newer (Langstroth) hive, have enjoyed success this 2017: queens producing plenty of brood and workers creating generous amounts of comb and honey.

But it’s been a mixed-bag 2017 for our backyard honeybees.

At the beginning of spring, Buzz was queen right (meaning that she had a healthy queen), but by April, we saw no brood, which means the queen isn’t laying eggs, which means that the hive is no longer queen right. We requeened Buzz–twice, in fact–but the hive continued broodless, and without brood, there is no new generation of honeybees to carry on the tasks of the hive. One long-time beekeeper suggested that perhaps Buzz had developed laying workers, which happens when a hive is queenless for a period of time. Worker bees can lay eggs, but the eggs aren’t fertilized, so no larvae develop, and when there are no new larvae, there are no new adult bees.

Honeybees need their queens.

Laying workers are a particularly difficult problem in a hive and what I learned indicated that once that situation is in play, there’s little a beekeeper can do–the bees will continue killing any introduced “real” queen, and laying workers don’t produce fertilized brood, so the stage is set for a dying hive.

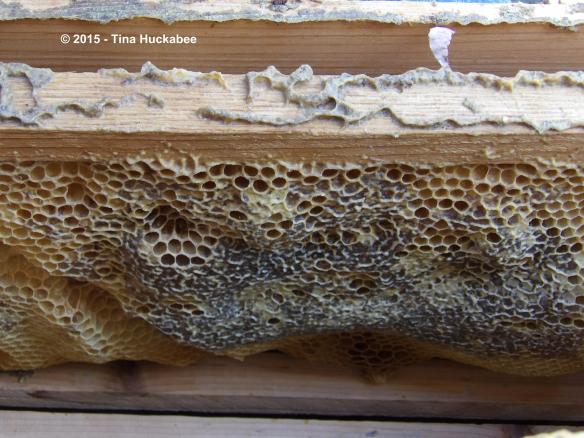

By late June, we accepted that Buzz was done; the gals would live out their lives and the hive would die. It was a sad conclusion, but we did what we could for Buzz in re-queening and were out of options. We went about our summer life and should have checked the hive in late July or early August for any problems, but didn’t: some travel, some stormy weekends, and some laziness all conspired to delay our beekeepers’ responsiblity of checking the hive during that period. In late August, we finally checked Buzz and horror met us: Buzz was crawling with the foul and disgusting adults and larvae of the Wax Moth, Achroia grisella. The comb was riddled with creepy-crawlies, nasty frass, and blackened, mutilated comb. There were only about a dozen bees remaining in Buzz; the lassies had no comb, pollen, or honey stores left undamaged by the moths and their offspring. We were so appalled at the sight that we immediately and completely dismantled the hive, packaging the frames in plastic trash bags for disposal and undertaking a (somewhat) cathartic wax moth/wax moth larvae killing spree.

Wax Moths are an invasive insect which do great damage to a hive, but are usually only a problem if the hive is weak.

Yup, that pretty much describes Buzz.

Poor, poor Buzz. I guess we should have attempted to dump some of Buzz’s honeybees into Woody earlier in the summer, but we didn’t. Up until that last few weeks, we were checking Buzz regularly and while it was clear that there were fewer and fewer bees at each check, Buzz was buzzing. Apparently, the moths moved in during the August checking dearth, and in short order, totally devastated Buzz.

We worked intensely to rid the hideous invaders from the hive and there was no time for photos of the mess that became Buzz’s innards. The larvae, moths and resulting hive damage was gross–really gross–so we worked quickly to get the job done. If you want a peek-n-read about this nasty-to-honeybees critter, check out this article from Texas Apiary Inspection Service.

Buzz now sits, forlorn and alone.

I moved the empty Buzz away from Scar and Woody. I didn’t want Buzz’s cooties near the other two hives. There’s nothing scientific about this, just my weirdness.

What’s left is a bit of Wax Moth webbing decorated by larval frass (poop, for the uninitiated).

The inside of the hive is downright pristine, compared to what it was when we discovered the wax moths, larvae and resulting damage.

I need to clean Buzz (vigorous scrubbing with chlorine, water, and a brush should do the trick), and once that’s done, she’ll be ready to host and house another package of honeybees with a young and healthy queen; that’s on tap for mid-April.

As for the other two hives, the news is much better. Scar–who we thought was a queenless hive at the beginning of 2017–not only had a queen but a wildly, massively egg-laying queen! Every time we’ve check Scar, fresh brood and loads honey met with our inspections. During summer, we took 8 full top-bars of honey, yielding a gallon and a half of honey.

Yum! After crushing the comb and dripping the honey into jars, I always set out the crushed comb for the bees’ slurping pleasure. There’s plenty of honey that I can’t get to and I don’t want it wasted. The honeybees should have it as because they’re the heroines of honey.

It doesn’t take long for honeybees to strip the comb of any available, edible honey, leaving dry comb which I dump into the compost bin.

This year we’ve kept our promise to be vigilant varroa mite inspectors and undertook four varroa checks in all three hives.

After shaking a half-cup of guinea-pig honeybees with powdered sugar, we pour them back into their hive, where, due to their sugary coating, they become everyone’s BFFs.

Scar won the prize for most varroa mites.

Varroa mites are tiny, oval, and red-brown in color. The powdered sugar on the bees, combined with the shaking of the bottle, sloughs off any varroa attached to bees. We shake the sugar onto a white plate, spritz with water, and count varroa mites.

Even so, there were not enough varroa in any hive check (there must be over 3% varroa found per total population of bees–yes, some math is involved here…), to require treatment, which is definitely a win for the honeybees and their keepers.

The honeys (and occasional buddies) enjoyed leftover powdered sugar!

The honeybees have had a busy year. What have they done in their spare moments when not tending brood and producing comb and honey? Performance art, of course!

Silly honeybees!

So closes our fourth full year of keeping–and learning about–honeybees. We remain entranced with them, marveling at their work ethic and swooning at their honey. We confess an affection for them (even when we get stung!) and an appreciation for their life cycle and place in our eco-system.

I’m grateful for their year-round work and partnership with me in the garden.