As nature does when days grow longer and temperatures warmer, spring brings tender baby leaves which soon grow big and plump buds with unfolding petals. Wildlife is energized and preoccupied with family responsibilities, and insects emerge from dormancy, also preparing for their next generation.

Blue Orchard bees, Osmia lignaria, have materialized in my garden this past week. They are blue, buzzing, and beautiful.

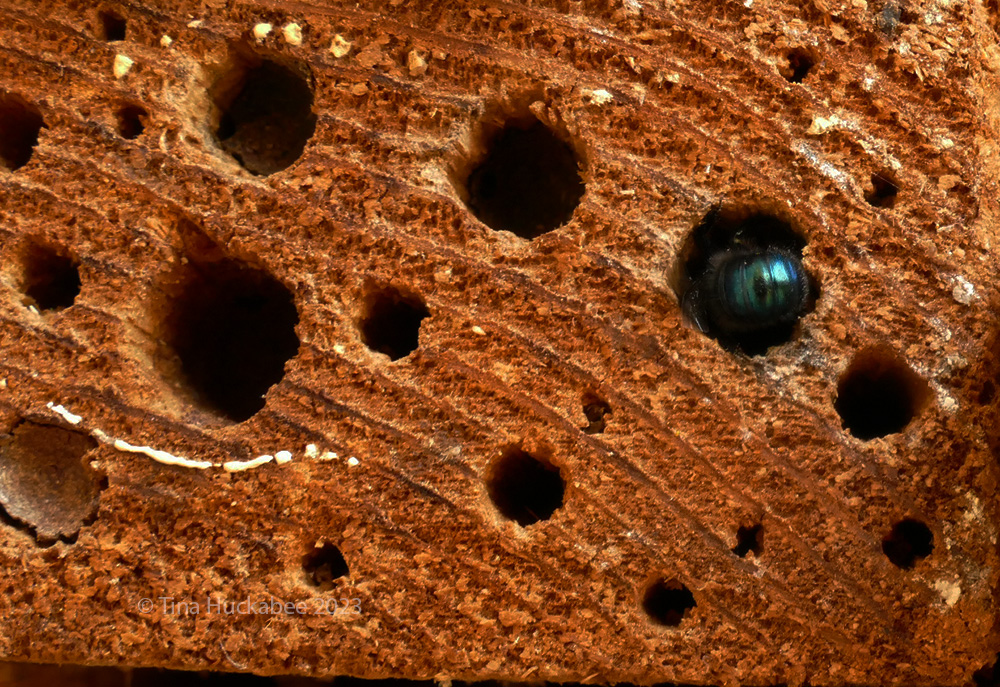

The adult Blue bees flying around now are the eggs laid and hatched a year ago. These are solitary bees and unlike honeybees, not part of a hive. Females lay their eggs in holes of wood or masonry and don’t have a crew of sisters to care for them. The adults prepare the nests by gathering a mix of pollen and nectar known as “bee bread” and then lay their eggs on that bread to nurture the larvae once hatched. Each egg is sequestered in its own room to grow and develop, each room separated by a mud-n-leaf matter wall. Female eggs are laid in the deep end of the hole, the male eggs toward the front of the hole.

Another difference between honeybees and Blue bees (as well as other native bees) is that the Blue bees carry pollen on their abdomens, rather than on their leg pockets or corbiculae as honeybees do.

It’s been a good spring for these bees, more activity than I recall from last year. I’ve seen many working around the Martha Gonzales roses, nibbling leaves to add to the nest sites.

These are such gorgeous bees! They’re fast flyers though and always on the move, which is challenging for clear photos. As I observe and attempt to photograph, these bees are blue flashes, sparkling in the sun.

Near this bee apartment, made from untreated wood with drilled holes and bamboo tubes, there is constant activity, flying in, zooming out, and dotting the wood with metallic color.

Blue Orchard bees are used in commercial farming because they’re excellent pollinators, besting the beloved honeybees. I’m happy that they found my garden and each early spring add to its life and activity–and beauty.

It’s easy to attract these and other wonderful native bees to your garden. Plant a variety of native flowers that bloom throughout the growing season; provide water, some shade, and dried wood, like large limbs from shrubs or trees. I don’t stack my wood piles, but lay the wood randomly (mostly in the back of my gardens) so that rats don’t have a safe place to set up their homes. Leave some area of your place on the Earth free of grass and garden so that there is available bare soil for ground nesters. Don’t use pesticides.

You can also build bee houses, too.

While bee houses or hotels aren’t as labor intensive as honeybee keeping, it’s still a good idea to clean out or replace (if using bamboo) the holes annually so that fungal and parasite problems are avoided. There are plenty of online resources and information for attracting native bees and giving them a safe place live out their lives. County Master Gardener groups, botanic gardens, and native plant groups are just some of the organizations promoting the inclusion of native bees in home gardens. Wherever you live, you can access information for your region on native bees and their habits. If you’re in Texas, check out these links to learn more and there’s lots more out there!

https://citybugs.tamu.edu/2018/06/11/caring-about-the-other-bees/

https://txmg.org/denton/north-texas-gardening/community-gardening/about-texas-native-bees/

https://biodiversity.utexas.edu/news/entry/leafcutter-bee-nest