Recently I read the delightful biography about and chronicle of Beatrix Potter and her life as a gardener and naturalist: Beatrix Potter’s Gardening Life, by Marta Mcdowell. Most people know Beatrix Potter through her “Peter Rabbit” series of children’s books, but she was also an important conservationist whose land comprises most of the Lake District National Park in Great Britain. In one chapter of Beatrix Potter’s Gardening Life, McDowell is discussing Potter’s penchant for a garden “makeover.” McDowell called that need for change in the garden “a permanent impermanence.” Those who garden understand that gardens are journeys, not destinations. We continually amend and refresh sections or entire gardens and for many different reasons. We augment our gardens because of overgrown plants or development of too much or too little shade or sun. We refine our gardens as our aesthetic choices evolve or because we want plants appropriate for the changing needs or conditions of our gardens.

Earlier this spring, I decided to remove all of the Berkeley Sedge, Carex divulsa, that I had planted in my gardens.

I discovered Berkeley Sedge while employed at the Green Garden at Zilker Botanical Garden and liked its hardiness, evergreen growing habit and attractive seed-heads. I bought small pots and planted them in various places on my property.

In the first few years, I was pleased with the sedge; it added structure and foliage interest and Berkeley Sedge is drought tolerant.

There is a garden space in the Green Garden titled “Hill Country Shade” in which scads of Berkeley Sedge seeded out. Aside from the fact that I philosophically disagreed with the non-native Berkeley Sedge planted in a garden touted as “native,” I also found I was constantly weeding out the seedlings produced by those sedge plants. It was one of the more persistent chores of that job–pulling one seedling up, it seemed as if six more appeared. One winter day, I met a California landscape designer and we visited about that plant. She mentioned that the Berkeley Sedge was labeled as invasive in California and asked if it was labeled so here in Texas. I later checked and according to TexasInvasives.org Berkeley Sedge, Carex divulsa, is not considered an invasive plant in Texas. San Marcos Growers in California originally tagged Berkeley Sedge as a native, later concluding that it is not a native sedge. A quick Google search shows two different sites, Pacific Horticulture and californiabotany.blogspot.com which state definitively that this plant is an invasive non-native and spreading throughout California.

Back to my gardens. After several growing seasons in which those attractive seed-heads developed and dropped seed, I noticed baby Berkeley Sedge everywhere.

Obviously, the density of seedlings was greatest near the spots where the sedge was growing, but I’ve found rogue seedlings in all parts of my gardens. I water my gardens infrequently and for several groups of Berkeley Sedge, the only water received comes from the sky. And still, lots of seedlings.

I’m in the process of pulling those seedlings as I see them and as new seedlings develop, but it will take some time.

To be clear, I have other plants that could be described as invasive:

Heartleaf Skullcap, Scutellaria ovata ssp. bracteata,

definitely qualifies as an aggressive grower and invader!

Yarrow, Achillea millefolium,

spreads magnificently.

I continually weed out the always obnoxious, except when beautiful, Inland Sea Oats, Chasmanthium latifolium.

And the ubiquitous (in my gardens), Lyreleaf Sage, Salvia lyrata, appears throughout my property.

These plants seed out or spread and I don’t mind. Perhaps I’m more tolerant of these particular “invasive” plants because they are all native to this area–they belong here and I’ve cultivated a situation in which they thrive. I use them as I see fit in the garden–pulling them up where I don’t want them and transplanting them where I do. I am a practitioner of the constant refreshing and reworking which is that gardeners’ creed of permanent impermanence. I have no choice. The garden is dynamic– an organism in perpetual, organic motion, responding to environmental changes and sometimes, gardener whimsy.

Or not. I routinely pass plants which spread to other gardeners or toss unwanted seedlings in the compost for future use as soil amendments. But with the Berkley Sedge, I decided that I didn’t want a non-native to become a pest plant in my gardens or possibly, surrounding landscapes. Much like my decision to remove the Berkeley Sedge in the “Hill Country Native” space, I removed a potentially aggressive plant because of my concern about its spread and because I prefer to use mostly native and non-invasive non-natives in my personal gardens. Taking out the sedge and adding “new” plants to the area will alter the feel of those spots–adding blooms and varying foliage.

One of my last projects at the Green Garden was removing the Berkeley Sedge in the “Hill Country Native” garden and transplanting as much as possible to a formal, rocked in space, located in deep shade, to serve as a demonstration of a low water lawn alternative to the water-hogging St. Augustine grass so common here in Texas. Despite some misgivings about Berkley Sedge in a garden, I think it has value as a an alternative “grass” lawn–especially if the seed heads are kept in check and not allowed prolific procreation. I haven’t visited ZBG since leaving that job a year ago, so I don’t know how that Berkeley Sedge lawn has fared, but I’ll bet it’s growing well. I only hope it isn’t spreading too much.

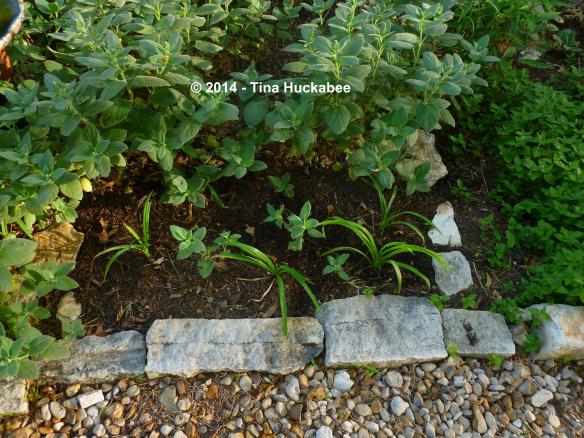

Removing the Berkeley Sedge in my gardens allows me the opportunity to rethink some small sections of larger garden spaces. I didn’t run out and purchase anything new, I dug up and separated favorites from my gardens and recycled them in place of the sedge. I’ve planted Heartleaf Skullcap paired with a common, non-native pass-along day lily,

…some lovely native Yarrow,

…and native to West Texas, Mexican Feathergrass, Nassella tenuisima.

I love all of these plants and use them repeatedly in pockets throughout my gardens. Each will require reining in at some point, but that will be another opportunity to observe, learn and experiment. And maybe, to garden with something new.

Permanent impermanence: As the Berkeley Sedge established and multiplied itself, I wrest control of the developing problem (as I defined it) and revised the landscape to better reflect my desires for my garden.

I’m not a purest, I grow many non-natives in my gardens. I transplanted a ‘Nana’ Nandina from a garden in which the signature plant, Barbados Cherry, froze completely this past winter. When I thought the Barbados Cherry died, I welcomed the opportunity to diversify and redesigned the garden with a more varied set of native plants. In re-imagining that garden, I understood how out-of-place the ‘Nana’ would be,

so after I pulled up two more Berkeley Sedge in another section of the front garden, I transplanted the ‘Nana’ to that spot.

Permanent impermanence: I augmented two gardens to better reflect their evolution and my desires.

Several years ago, the native Texas Sedge, Carex texensis, moved into my front garden, but inconveniently and stubbornly, in a pathway. As part of my recent garden reconfiguration, I transplanted the Texas Sedge clumps to a different spot. They’ve struggled a bit, but I think they’ll survive.

The foliage is finer than the Berkeley Sedge and they aren’t as consistently evergreen– they were nipped by the last hard freeze on March 2. Texas sedge doesn’t spread rapidly, either. I don’t find them quite as attractive as the B. Sedge (sacrilege!) and I suspect that’s why they’re not commonly found in the commercial nursery trade. Pretty sells.

Constantly evolving, the garden reflects life and nothing is permanent. Conditions change and the gardener responds. Gardeners follow fads and styles of gardening, always longing for that newest, cool plant to pop the palette of the landscape, sometimes regretting that decision and action.

Tastes change. Styles change. Needs change. We learn as we garden and our gardens reflect our growth. Nothing in gardening is permanent.