Hill Country Penstemon (Penstemon triflorus) is one of my favorite spring bloomers and every spring I eagerly anticipate the bloom cycle of this striking plant. This penstemon is one of the larger species and is a showy one indeed.

The blooms are fuchsia red and bloom in pairs and the leaves are lance-shaped and are opposite along the stem. A slender and elegant plant at bloom time, the flowers of the Hill Country Penstemon are borne on spikes 2-3 feet tall. Blooming “normally” in April and May, this year, my group of four began their bloom cycle in early March, about a month earlier than the normative time period.

Endemic to the Texas Hill Country, its native distribution is throughout the Edwards Plateau.

The penstemon genus is a large group of plants native to North America. The term penstemon means “five stamen” because of the five stamens in each flower, one of which is long and often fuzzy or hairy. The hairy stamen looks as if it’s a hairy tongue sticking out of an open mouth, giving rise to a common and old-fashioned name for many penstemon plants,”beardtongue.”

Another common name for Hill Country Penstemon is Heller’s Beardtongue. Most penstemon plants have tubular shaped flowers with lip-like petals, two at the “top” and three on the “bottom” of the flower.

A neighbor gave me my first Hill Country Penstemon years ago and it was a reliable bloomer. I’d forgotten about it because a larger shrub, Cenizo (Leucophyllum candidum), grew tall and shaded it to the point that it hadn’t bloomed in a couple of years. When I began a re-landscape of my back garden in 2010, I moved the two I had and added two more–one from Barton Springs Nursery and one from the fall Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center’s plant sale.

Interestingly, I noticed that the Penstemon from the Wildflower Center (left in the photo above) was generally larger and taller than the others I had. The stem was thicker and the leaves were definitely larger. Once it bloomed, the flower was also different: larger, lighter in color and with more variegation.

Surprise!! But a nice surprise! I thought that it looked a little like the Wild Foxglove or Prairie Penstemon (P. cobaea). After reading a bit, I discovered that these two penstemons commonly hybridze with one another. I assume that is what this different looking penstemon is.

So I seem to have two similar plants: a true P. triflorus and and a hybrid thereof.

I’ve planted this group of Hill Country Penstemon at the edge of a large mixed perennial garden beside a pathway, so that I could enjoy their beauty, up close, without traipsing into the garden itself. I love to see pollinators at work,

and observe the penstemon blooms sticking their hairy tongues out at me as I amble by, coffee cup in hand.

While I like where I have my Hill Country Penstemons planted, this is a plant more appropriately placed in the center or back of a large perennial bed. In spring, the Penstemon bloom spikes grow taller than surrounding shrubs and perennials that have been pruned during winter.

Once the bloom cycle is finished, the plant develops seeds for the next generation. Because my Penstemons are planted at the edge of the garden and the bloom stalks fade in attractiveness as the plant is developing its seeds, I prune them back well before the seeds are ready to disperse. If I had them planted in the center or back of the garden, I could let them develop seeds because the other perennials and shrubs would partially camouflage the unattractiveness of the spent bloom spikes. That way, I could allow the seeds to develop and disperse, thus ensuring the propagation of more Hill Country Penstemon without sacrificing attractiveness in the garden. It was a calculated decision on my part to have them at the edge of the bed, but I haven’t had any seedlings from this plant because I prune it down for neatness sake. Once the spent bloom stalks are pruned to the ground, there is a rosette which stays green throughout the remainder of summer and into the fall and winter.

That said, the Hill Country Penstemon can be separated at the roots, so it’s propagated that way as well.

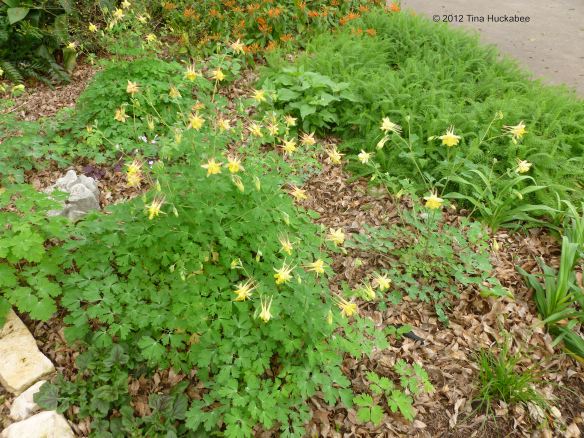

In a mixed perennial garden like this one,

it’s good to arrange a mix of sizes, shapes and bloom times so that there is layering effect of blooms, foliage and form interest.

I planted the four Hill Country Penstemons along with Blackfoot Daisy (Melampodium leucanthum) and Lyre-leaf Sage ( Salvia lyrata), which bloom in concert with the Penstemon. I’ve also planted some Iris (Shoshana’s Iris, I believe) next to the Penstemon to echo the spiky form. Unfortunately, the Iris didn’t bloom this year, but they are lovely with the Penstemon, blooms or not. I also have Purple Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea) planted in the same area, which will start blooming toward the end of the Penstemons’ bloom cycle and throughout the summer. Further behind and along either side of the Penstemon group, I’ve planted perennials with more shrub-like growth habits and (in general), longer bloom times. For example, just behind the Hill Country Penstemon are planted two Henri Duelberg Sage (Salvia farinacea ‘Henri Duelberg’), which will get 2 to 3 feet in height and width, several Rock Rose ( Pavonia lasiopetala), two white Autumn Sage (S. greggii) , two roses (Old Gay Hill and Martha Gonzales) and a Lindheimer’s (or Big) Muhly (Muhlenbergia lindeimeri).

The Hill Country Penstemon requires full sun and can tolerate rocky to heavy clay soils. It’s drought tolerant and a nectar source for bees and butterflies. In Austin, I’ve seen them for sale at Barton Springs Nursery and at the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center’s spring/fall plant sale.

Hill Country Penstemon is tough and so, so pretty. Even with her hairy, bearded tongue.